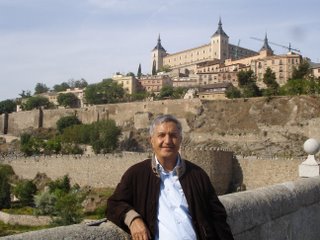

That’s what I thought to myself en route to Toledo, in the train, as we sped past rolling hills like the massive rounded waves of the open ocean, frozen into place. They were tinted crimson here on the crests of some, and there in the troughs of others, with carpets of May poppies. The other parts of the hills were covered with golden-green wild grasses, offset by the silvery sage color of the olive trees in the middle distance.

The train station was also a far-cry from the Toledo Amtrak station, to be sure. We were greeted by a station of painted tiles and carved wood, in a sort of baroque Islamic style. The station was situated at a slight distance from the town, which itself is perched on a high-hill carved out from the red rocks by a rapid river. As Daddy and I walked up, up and up toward Toledo, we walked through hedges of rose bushes in full bloom, fields of wild snapdragon, hollyhocks, sweet peas, and some vibrantly purple flower that grew in abundance and that I’ve never seen before.

With great satisfaction, our visit to Toledo permitted me to understand, at long last, the formerly mystifying expression: “holy Toledo”. It certainly came from the fact that Toledo was for a couple of centuries (I don’t retain dates well) the heart of the Catholic church in Spain. Before that, though, it was a sort of capital for the Visigoths, as well as apparently being a vital foothold for the Muslims in Europe during the Islamic presence in Spain. During that time it was also an important center of Jewish life and culture in Spain.

Both tellingly and sort of sadly there are few traces of anything left, religiously speaking, other than Catholicism. That being said, though there are “few” traces, there “are” traces of both the Jewish and Islamic presence, and I suppose for me that was the most interesting thing. With each press of my foot to the cobble-stoned streets, I was aware that I was probably walking on the same sacred stones that had witnessed the ebb and flow of so many distinct cultures over the centuries. The concept of erasure was also very striking to me—each culture that had come before was ‘erased’ by the next: the mosques and synagogues were largely turned into churches, and so convincingly that I had to search for the remains of what had existed before them. I suppose this is true of most, if not all places—the winners win, and install themselves with force, establishing their culture by obliterating aspects of others. But I have yet to determine why this notion was so much more powerful to me in “holy Toledo” than in other places I have been.